- Guerilla in film is a mindset: It’s about using limitations as a creative blueprint, not a barrier, driven by a “shoot first, ask for forgiveness later” ethos.

- Build for the finish: The most critical phase is pre-production. Design a story that is realistically achievable with the resources you actually have, ensuring you can complete the project.

- Embrace your constraints: Wear multiple hats, capture authentic textures from your environment, and know where to strategically invest in a professional finish (like color and sound) to make your work stand out.

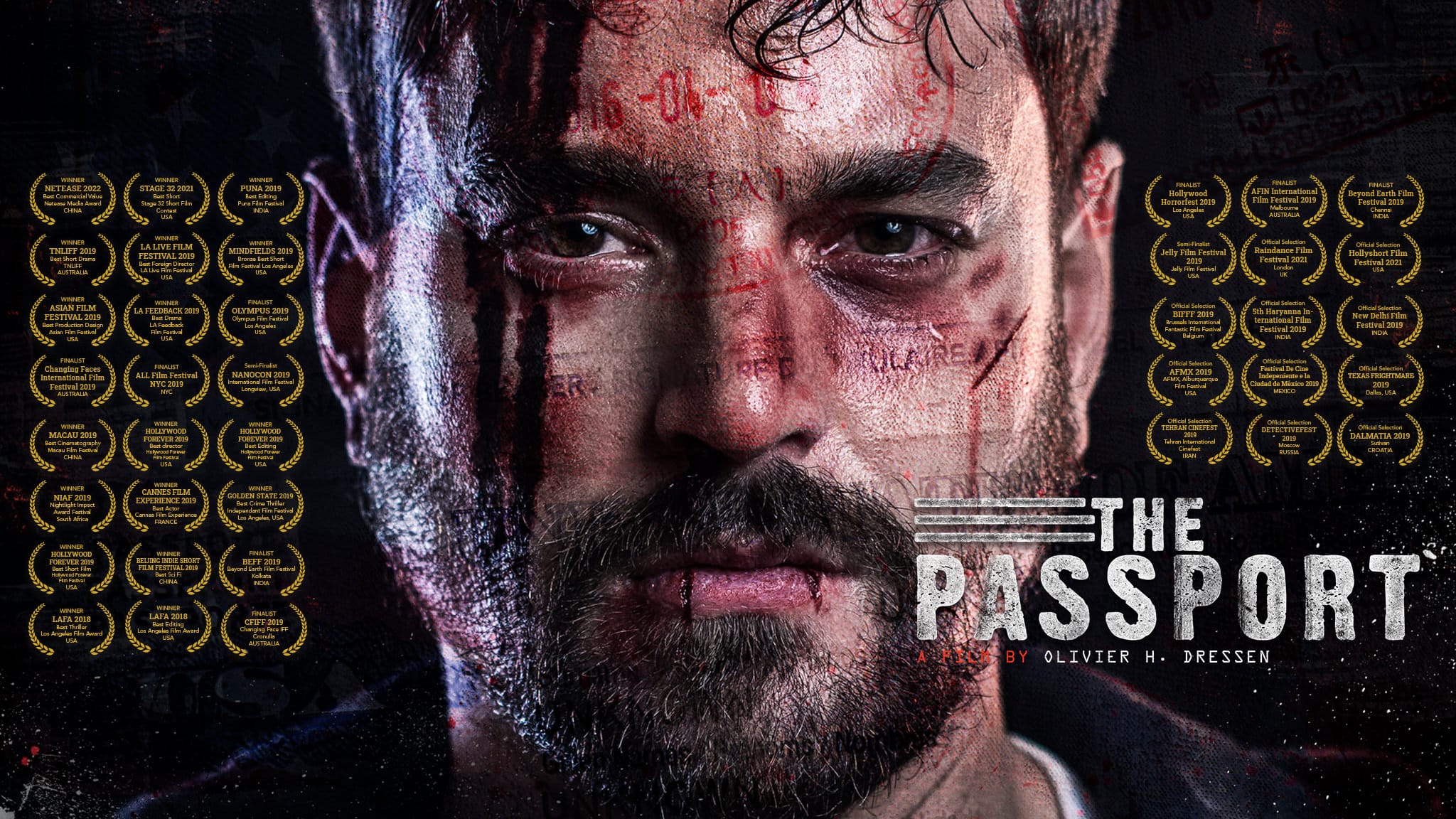

There’s a particular kind of creative hunger that I think every filmmaker recognizes. It’s that feeling deep in your gut that you have a story to tell, but you’re standing on the outside looking in, with no studio backing, no big budget, and no permission slip. Years ago, before I ever picked up a camera, I felt that same pull writing my name—’Hero’—on city walls. It was about making a mark with what I had: a can of paint and a bit of nerve. That same spirit is the absolute core of guerrilla filmmaking. It’s a philosophy born from necessity, a scrappy and audacious way of creating that says the most important thing is simply getting the film made. My 2018 short, The Passport, was forged in that fire, a 15-minute sci-fi thriller that became an unintentional masterclass in turning constraints into our greatest asset.

What is Guerilla Filmmaking?

At its heart, guerilla filmmaking is a rebellion against the idea that you need a green light from someone else to create. It’s a mindset that prioritizes ingenuity over inventory. This approach often involves shooting in public locations without permits, working with a skeleton crew who can adapt on the fly, and using the world around you as a living, breathing set. It’s less about the gear you have and more about the resourcefulness you bring. For our team on The Passport, this wasn’t just a style; it was our entire production model. The film, a Belgium/China co-production shot on the streets of Shanghai, had no studio pipeline or safety net. It was willed into existence by a handful of people who believed that the story—a neo-noir puzzle about fractured identity guided by the line, “You are what you remember”—was the only currency that truly mattered.

This approach is part of a rich tradition of independent cinema. It’s the spirit of Robert Rodriguez shooting El Mariachi for $7,000, using a wheelchair for dolly shots and casting local townspeople as actors. It’s the Duplass brothers making The Puffy Chair with a borrowed camera on a weekend road trip, forever changing the mumblecore scene. These filmmakers proved that a compelling narrative and a clear vision are more powerful than any studio budget. Their work, like ours, wasn’t about what they lacked; it was about what they could do with what they had. It’s a testament to the idea that limitations are not a cage but a canvas, forcing you to find more interesting, authentic, and often more powerful ways to tell your story.

So why does this matter more than ever for creatives today? Because the technical barriers to entry have all but vanished. We have 4K cameras in our pockets and professional-grade editing software on our laptops. The challenge is no longer access to tools, but a crisis of permission—we wait for the perfect script, the right funding, or the ideal collaborator. The practical lesson here is to stop waiting. Instead of focusing on what you don’t have, take a radical inventory of what you do. Do you have access to an interesting old warehouse? A friend who is a talented musician? A unique family heirloom? Build your story around that one, undeniable asset. That is the true start of guerilla filmmaking.

Pre-Production: Designing a Film You Can Actually Finish

The most common reason indie films fail is that they die long before the cameras ever roll. They are crushed under the weight of their own ambition. The most crucial lesson we learned from The Passport is the discipline of “building for the finish.” This means that from the moment you start outlining, your primary goal is to design a story that you can realistically complete. Co-writer/star Michael Koltes and I didn’t just dream up a sci-fi thriller; we meticulously engineered it to survive the brutal realities of our resources. We saw our limitations—a tight schedule, a micro-budget, and a handful of accessible locations in Shanghai—not as roadblocks, but as the foundational pillars of our narrative.

We reverse-engineered our script from our assets. We knew we had access to the moody, rain-slicked backstreets of Shanghai, so we wrote scenes that leaned into that neo-noir aesthetic. We knew Michael could deliver a powerful, internalized performance, so we built the story around his character’s psychological unraveling, minimizing the need for large-scale set pieces. This process is about making strategic creative choices that align with your logistical reality. Today, this can be supercharged with tools that didn’t exist for us back then. You can use AI to rapidly visualize concepts and create storyboards, mapping out your entire film before spending a single dollar. A tool like our Midjourney Mastery Guide can show you how to build a visual playbook that ensures your vision is achievable. After we locked our script, we went from final draft to principal photography in just three weeks, a velocity that kept the creative momentum alive.

This principle of “building for the finish” is the single most important mindset shift for an emerging filmmaker. It’s about killing your darlings before they kill your project. Your practical takeaway is to create a “Resource Inventory” before you write a single word of your screenplay. Make two columns. In the first, list every single asset you have access to for free: actors, locations, props, vehicles, special skills within your friend group. In the second column, list your limitations: no money for permits, only able to shoot on weekends, no access to lighting gear. Let this document be your creative bible. This framework forces you to write a story that is not only personal and compelling but, most importantly, finishable.

Production & Post: Embracing Limitations and Wearing Many Hats

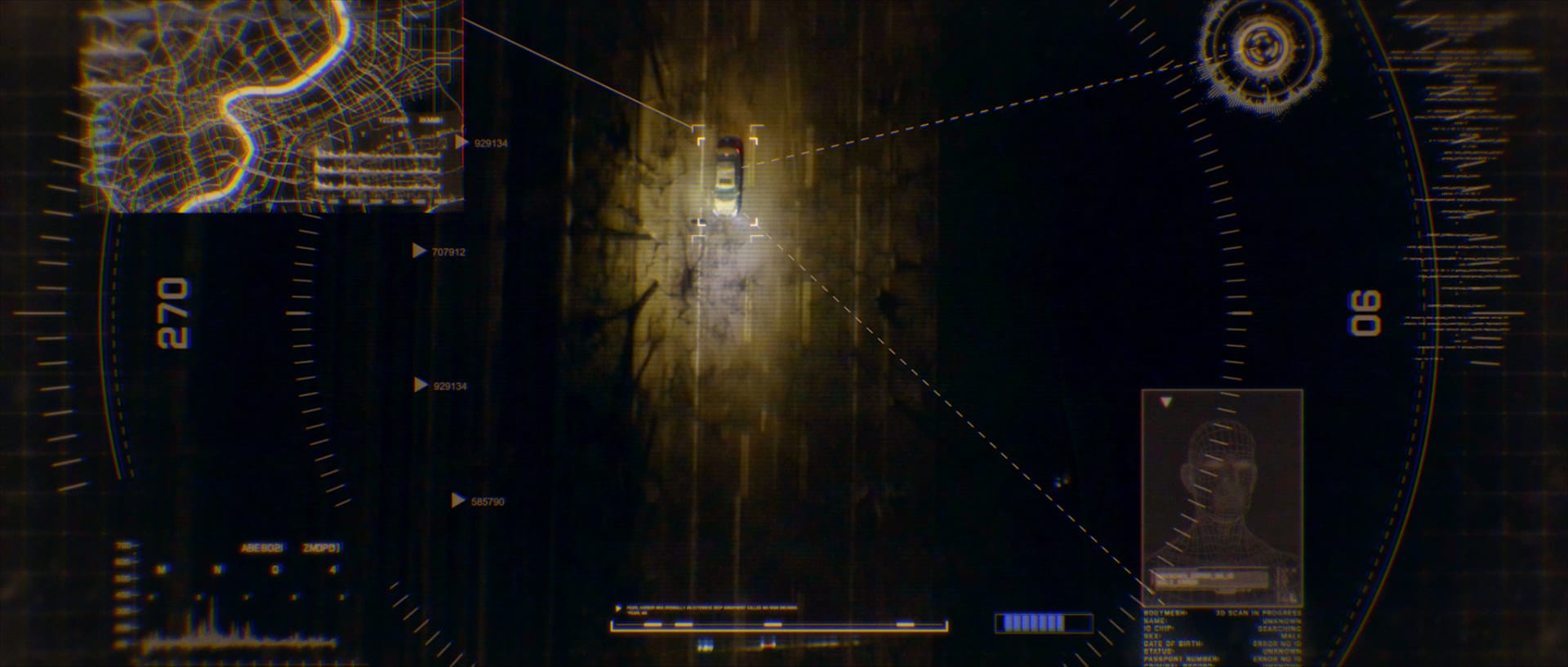

On a guerilla film set, your job title is more of a friendly suggestion. To get The Passport made, I had to be the director, executive producer, VFX supervisor, and even the poster photographer. This isn’t an ego trip; it’s a matter of survival. While this level of responsibility can absolutely lead to burnout—I think sleep became a distant rumor for most of us during that time—it offers an incredible benefit: a singular, undiluted vision. When the same person who wrote the scene is also supervising the visual effects and approving the final color, every decision serves the same story. There are no departments pulling in different directions; there is only the film.

This hands-on ethos extended deep into our post-production. To give our sci-fi world an authentic, textured feel, we didn’t rely on stock sound libraries. We went back out into the city with a field recording kit and captured the real sounds of Shanghai—the specific drip of water in a subterranean tunnel, the unique electrical hum of the city at 3 AM, the distant chatter echoing through an alley. These details cost nothing but our time, but they bought us a layer of truthfulness that money simply can’t. Yet, we also understood where our DIY approach needed to end. We knew that to compete on the festival circuit, our film needed a professional spine. We took the project to post-production houses in Belgium for a professional sound design and final color grade. This was our strategic investment, the decision to “finish like a grown-up,” and it made all the difference in elevating our scrappy short into a cinematic experience.

The ultimate lesson here is about balance. Embracing limitations teaches you every facet of your craft, from sound design to color theory, making you a more holistic and resourceful filmmaker. The practical tip is to identify your “non-negotiable” element of quality. Look at your project and ask: what is the one thing that, if done professionally, will elevate everything else? For some, it might be a powerful musical score. For others, it’s a flawless color grade. For us, it was both color and sound. Even on a shoestring budget, you must be willing to beg, borrow, or strategically allocate funds to that one key area. It’s the final 10% of polish that makes 100% of the difference to an audience. It shows you respect their time and your own craft.

From Scrappy Short to the Big Screen: Making Your Film Travel

When we finally exported the master file for The Passport, our only goal was to have a finished film we could be proud of. What happened next was a complete surprise. The film began an incredible journey on the festival circuit, ultimately gathering over 60 nominations and 20 wins in categories like best short, best director, and best thriller. The absolute peak of this run was seeing our self-funded, clandestine film screen at the legendary TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. Standing there, I was hit with the profound realization that work born in alleyways and edited on laptops can find its way to the same screens that premiered Hollywood’s greatest epics. It was a powerful reminder that a good story, well-executed, will always find its audience.

This journey transformed the film from a passion project into a powerful calling card for our entire team. A review from the LA Film Awards, which called it “thrilling throughout … with excellent performances and impressive visual effects,” became an invaluable piece of validation. The festival wins and positive press proved to the industry not just that we could tell a story, but that we could see a project through to a high-quality finish and get it in front of people. This is the true power of guerilla filmmaking: it’s not just about making a single film; it’s about building a tangible body of work that demonstrates your voice, your vision, and your resilience as a creator. It opens doors that were previously locked.

For any filmmaker out there feeling stuck, the journey of The Passport is meant to be a roadmap, not a rare exception. Your film is your resume. A finished short that travels to even a handful of small festivals is infinitely more valuable than a brilliant feature script gathering dust on your hard drive. The practical advice is to think about distribution from day one. As you enter post-production, start building your electronic press kit (EPK). Design a compelling poster, write a sharp synopsis, take high-quality stills, and craft a thoughtful director’s statement. Research festivals that align with your film’s genre and budget. Having this package ready to go means that the moment your film is finished, you can immediately start getting it out into the world. You don’t need anyone’s permission to start.

Internal Links for Further Learning

- Explore how to rapidly visualize your film with our Midjourney Mastery Guide.

- Learn about modern production techniques in our guide to Filmmaking AI Workflows.

- Discover how to create stunning visuals on a budget with Generative AI Made Easy with AI Render Pro.

Conclusion

The path of guerilla filmmaking is challenging, exhausting, and often uncertain. But it is also the most direct and honest way to find your voice as a filmmaker. It teaches you that your most valuable assets are your creativity, your resourcefulness, and your resolve. The Passport taught me that limitations are not something to be overcome, but something to be embraced as a guiding force. They push you toward more elegant, innovative, and personal solutions. So, I’ll leave you with a question: what’s the one story you could tell right now, using only what you have within arm’s reach?

If you’re looking for tools to help you build those stories faster and more visually, check out my prompt manual, AI Render Pro. It’s designed to help creatives like us bring our visions to life.

For more informations, go visit Studio Supreme Films.

FAQ

What is the main principle of guerilla filmmaking?

The main principle is resourcefulness. It’s a filmmaking philosophy focused on using a low budget, a small crew, and available locations to create a film, prioritizing ingenuity and speed over traditional, permission-based production models.

Can you do guerilla filmmaking with a smartphone?

Absolutely. Modern smartphones shoot in high-quality 4K, and with the addition of a few inexpensive accessories like a microphone and a stabilizer, they can be incredibly powerful tools for a guerilla filmmaker, as seen in films like Sean Baker’s Tangerine.

How do you handle post-production on a guerilla film?

Post-production is often a mix of DIY and strategic investment. Many tasks like editing and basic VFX can be done on personal computers. However, for maximum impact, it’s wise to invest in professional sound design and color grading to give your film a polished, cinematic feel.

Discover more from Olivier Hero Dressen Blog: Filmmaking & Creative Tech

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.